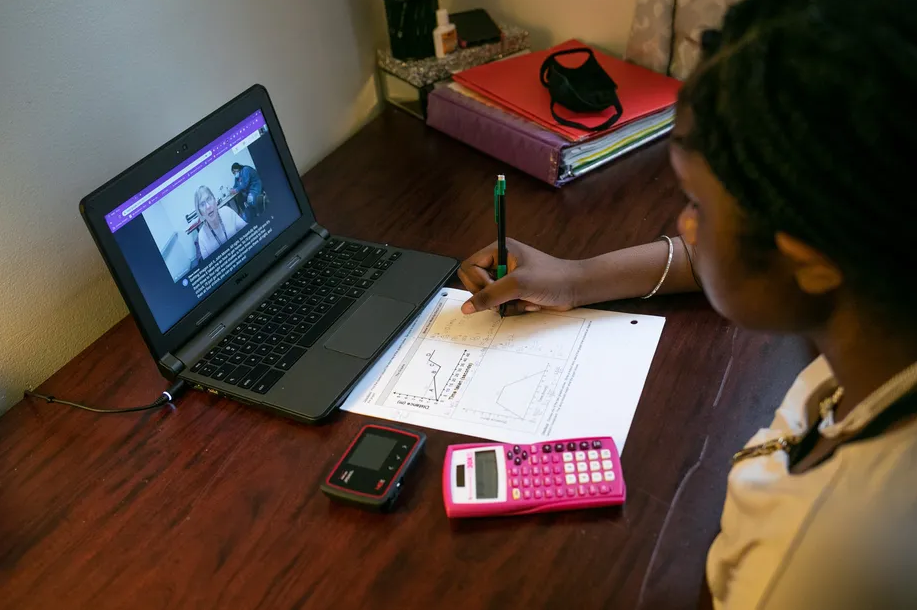

In San Diego, like in many school districts, virtual learning looks different this year.

Earlier in the pandemic, fully virtual students were paired with teachers at their home schools who guided them through a full day of classes — from math to gym — often alongside their pre-pandemic classmates.

But this year, after the state prohibited that kind of remote learning, San Diego launched a standalone virtual academy with its own virtual teachers. Students get some live instruction and teacher check-ins, then spend the rest of the time doing work on their own.

Another change? The level of interest. Last year, 44% of students ended the year online. But so far, less than 1% have chosen the virtual academy, though the district is still working through applications.

It was never a question that enrollment in virtual options nationwide would be lower this year, as schools promised a return to relatively normal operations. The availability of vaccines for adults and older students has alleviated some health concerns, many students are weary of virtual school, and pediatricians, federal officials, and school leaders have urged families to send their children to school in person. Several states and school districts also prohibited or severely limited virtual options.

But some families still clamored for remote learning, often because they had immunocompromised family members or young children who weren’t yet eligible for a vaccine. And many districts that serve big cities are offering virtual school, at least for some students — raising questions about exactly how many would continue to learn online this year.

The answer appears to be relatively few, for now.

In Philadelphia, for example, just over 1% of students transferred into the district’s virtual academy this year. In Charlotte-Mecklenburg schools, less than 2% of students chose the virtual option. A Chalkbeat survey of 10 Colorado districts last month, including Denver, found that between 1% and 2% of students had picked remote options, though districts cautioned that their numbers were still in flux. In Los Angeles, just over 2% of students have enrolled so far in the district’s virtual independent study, though some students are still waiting to have requests processed.

In Gwinnett County, Georgia and Duval County, Florida, about 3% of students chose online learning. And in Des Moines, Iowa, about 5% of students went with that option.

Those numbers represent a substantive change from pre-pandemic patterns, and some may tick up. But overall, enthusiasm for the virtual learning options available now appears muted.

The reasons why vary, but some families found these virtual options less appealing when they were spun off from their child’s school — sometimes resulting in less socialization and live instruction for students.

Becky Duffy, a parent in Des Moines, changed course after initially signing her first grader up for the district’s virtual option once she realized how different it would be.

Her daughter did well with virtual kindergarten, and she thought keeping her online could lower the risk that her 3-year-old, who had lung problems when she was born, could be exposed to COVID, since her state doesn’t allow schools to mandate masks. But last year, her daughter learned virtually alongside her classmates and built a relationship with her classroom teacher. This year, an outside company is running the program, and her daughter wouldn’t have had much interaction with an adult or her peers.

“If we would have had a dedicated teacher and there were more kids in her class and there were more people in the neighborhood who were doing it, I think it would have been a lot easier to make that choice,” she said. “When you’re all in the same boat for virtual learning, too, it’s a little different than if you’re just going at it alone.”

Bree Dusseault, an analyst at the Center for Reinventing Public Education who’s tracking 100 large districts’ back-to-school plans, has found that more than half of them are offering a remote option to all students, which tends to be a standalone program. Eighteen of the districts ask students to give up their seat in their home school.

“Their remote learning programs are not the core focus,” Dusseault said. “They’re often parallel programs to the in-person experience.”

For other parents, the way the virtual programs were set up made it difficult or impossible to enroll. Some districts capped enrollment or limited availability to students in certain grades or children with certain medical conditions. Other districts required families to talk with a staffer first, sometimes counseling them against signing up.

In Madison, Wisconsin, for example, only students in middle and high school could apply for the district’s new standalone virtual learning program. Students had to answer a series of essay questions to get in, including one about how they planned to overcome any virtual learning obstacles. The district received 452 applications, but accepted half — meaning, at most, around 1% of students will be enrolled.

Some districts offered short sign-up windows for virtual programs they hadn’t intended to offer.

In Texas, after Arlington Independent School District said it didn’t plan to offer a fully virtual option this year, Maria Juarez decided to homeschool her children. She had at-home lessons ready to go when her district announced a temporary remote option — and gave parents one day to enroll.

She rushed to sign up her children, who are in pre-kindergarten, first grade, and fifth grade. Juarez says she’ll give it a chance, but already she has concerns. She was told her kids wouldn’t get the virtual arts and dual language classes they took last year. Her two older children, who have individualized education programs, could only get the speech services and one-on-one extra help they got during the day last year after school.

“It’s basically you’re teaching yourself,” she said. “I feel like it’s really unfair. Last year, I feel like they knew how they were going to take care of things.”

Demand may continue to shift. A nationally representative survey of parents released Wednesday found that as the summer went on and virus cases rose, the percentage of parents who wanted full-time or part-time remote options had risen to 57%. Demand was highest among Hispanic and Black parents.

In some cities, like Memphis, a growing number of parents are pushing district officials to create a virtual option. Tennessee has the highest COVID case rate in the country, but officials there have put restrictions on virtual learning, and are only granting temporary waivers in limited cases.

“We don’t have a lot of viable options,” said Memphis parent Sara Corum, who expressed concern about sending her children back in person after they were exposed to COVID and had to quarantine at home. “No parent should ever be in the position we’re in. Ever.”

COVID vaccines for children under 12 may still be a ways off, and a chunk of parents don’t intend to inoculate their younger kids. But still, some families say they won’t need a virtual option anymore when their children can get shots.

Laura Coyle signed her first grader up for Des Moines’ self-paced virtual option, but allowed her 12 year old, who’s fully vaccinated, to go back in person if he wore a mask. She was swayed when he told her “how difficult it was for him emotionally and mentally to feel isolated and not to be around other children.”

Her daughter wanted to go to school in-person, too, but it’s off the table until she can be vaccinated. Even then, Coyle isn’t 100% sure.

“I still feel uncomfortable about it because I know not everybody is masking and vaccinated,” she said. But she knows it could help “balance out with her emotional and mental well-being.”

This article was originally posted on As virtual options split off from traditional school, interest dips

More Stories

More West Virginia schools will participate in opioid abuse prevention program

Pennsylvania is increasingly underfunding special education, report finds

Memphis’ Kingsbury High School community steps up call for changes