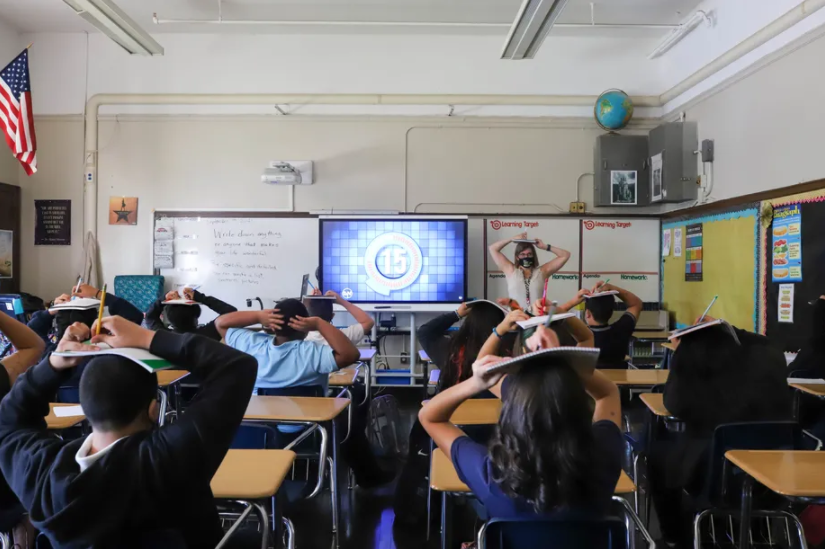

With COVID surging and a growing number of schools shifting to virtual learning, the first seven days of 2022 have provided an unsettling preview of what’s to come in education this year, when the continued struggle to recover from the pandemic will dominate.

COVID, and its effects on schools, is by far the top education issue of 2022. It permeates every aspect of how students learn, teachers teach, and schools operate.

So far this year, more than a dozen Michigan school districts have temporarily shifted to online learning as the more contagious omicron variant has fueled big increases in positive cases. While most districts returned to in-person learning as scheduled after the break, there is growing uncertainty about whether they’ll be forced online in the near future. And, the surge is refueling debates about policies making the wearing of masks optional or required in school buildings.

Chalkbeat talked to Michigan education policy experts, educators, and researchers to help identify the top education issues of 2022. Here are topics we’ll be closely following.

Anything missing? Tell us at [email protected].

Can students rebound?

As we head into the second half of the school year, the biggest question is: Will the current surge slow or stall efforts to help students recover from the previous school year, when some students spent much of the time learning online, and many others bounced between virtual and in-person learning?

Pandemic learning has been particularly difficult for some groups of students, including those with disabilities who didn’t receive all the services they require to learn, and students from low-income homes, who were more likely to learn online. Research has found students who learned online, including those from low-income homes, didn’t learn as much as those who were in person.

A key test will be whether educators are able to help students get back on track who fell behind.

“The stakes are high,” and include “the future of each and every student’s job opportunities and life outcomes, as well as states’ economic futures and talent workforce,” said Amber Arellano, executive director of the Education Trust-Midwest, an education research and advocacy organization based in Royal Oak.

Just as much is at stake in addressing the mental health and social challenges students have experienced while living through the pandemic. Students have spent so much time separated from their friends, experienced loss, and most recently, dealt with the threat of school violence that emerged after the deadly shooting at Oxford High School in November.

“If we don’t help kids to recover socially and emotionally in our schools, they’re not going to get those services elsewhere, at least not equitably,” said Katharine Strunk, a professor of education policy at Michigan State University. “Families who can afford help will get it, but those who can’t, won’t, and that will exacerbate inequities.”

It’s a “huge, defining moment,” said Strunk, because “if we don’t help kids to feel safe again, we could really be seeing long-term problems, not just for these kids, but for society.”

Will COVID relief money help?

Another big test of the year will be whether district leaders are able to use $6.1 billion in federal COVID relief money to help students catch up academically, address the mental health challenges, and confront a number of issues related to students and staff.

Many are using the money to hire teachers and pay them more in order to retain them. Others are investing in heating, air-conditioning, and ventilation systems. A lot are expanding summer school and after-school programs and investing in tutoring, technology, and counselors to help students with the pandemic’s social and emotional effects.

Reporters from Chalkbeat and the Detroit Free Press have teamed up to track how Michigan school districts are spending the money. In December, we reported that many districts haven’t clearly and publicly articulated their plans. That is concerning to education experts who say transparency, accountability, and community engagement are paramount.

“It was a mistake for the [U.S.] Department of Education not to build in a way to simplify the tracking of the monies being spent and make it available so the public can understand,” Strunk said. “The department had the opportunity to do it, and they didn’t.”

Although that spending is largely controlled by school districts, the governor has some role in steering it, and people will be watching, said Sarah Reckhow, a Michigan State University assistant professor of political science who specializes in education politics.

“(Gov. Gretchen) Whitmer can be proactive in her bully-pulpit role in pointing out examples of districts that spend recovery dollars wisely,” Reckhow said. “She can get guidance out to school districts to encourage them” to spend it on her priorities.

Equitable school funding

How well schools spend federal money, and how transparent they are, could impact perennial efforts to address Michigan’s school funding system. Several high-profile reports in recent years have concluded that the way the state funds schools isn’t adequate, and creates inequities between wealthy and poor districts. Whitmer has pushed for a more weighted funding system that would give additional state funds to the most vulnerable students. But a full-scale reform hasn’t happened. Could this be the year?

Arellano said that before the pandemic, national research showed Michigan ranked as one of the worst states in the country for gaps in funding equity.

“Fair funding is one of the most important enabling conditions for districts to create high-caliber, rigorous pathways of opportunity to learn at high levels,” she said. “As a state, we have failed tragically at creating these conditions for all children.”

Staffing woes continue to be a factor

Schools across Michigan have been strained by labor shortages – from teachers to support staff. Substitute teacher shortages, a problem before the pandemic, worsened so much this school year that lawmakers enacted new rules that make it easier for support staff such as bus drivers and school secretaries to cover classes. Meanwhile, school nutrition officials report shortages are making it tough to ensure students have access to quality meals on a regular basis.

The current COVID surge will only worsen the problems, because staff who are exposed to the virus or who contract it must be out of school buildings for at least five days or more.

The overall shortages are “going to plague us for at least four to five years and perhaps longer if the teacher incentives being proposed by a number of groups are not moved forward,” said Wendy Zdeb, executive director of the Michigan Association of Secondary School Principals.

“With wages rising in many other industries, along with better benefits and flexible working conditions, schools just can’t compete for workers,” Zdeb said. “This is going to cause serious staffing issues and it will require schools to function differently in the future.”

Education in the governor’s race

It’s unclear how big an issue education will be in the Michigan governor’s race. It wasn’t expected to factor heavily in the Virginia governor’s race last year but it ended up being key to Republican Glenn Youngkin’s win after a long campaign centered on energy, economy, and public safety. In the end, Youngkin rode a wave of conservative frustration over school mask mandates, delayed return to in-person learning, and instruction about race.

“If we read the tea leaves from Virginia, there are reasons to expect that education will be prominent” in the Michigan governor’s race as well, Reckhow said.

Whitmer, the incumbent Democrat, will likely take heat from Republicans who blame her for widespread school shifts to virtual instruction in the wake of the pandemic, even though she has only twice ordered schools shut down – at the start of the pandemic, and in the fall of 2020, when she ordered high schools closed for in-person instruction because of surges in positive cases. She and lawmakers negotiated in 2020 to give districts the flexibility to move learning online.

She is likely to tout her record of investment in schools including a massive expansion of the Great Start Readiness Program, the state’s free preschool program that now serves far more students thanks to federal COVID relief money.

Republicans, though, are likely to attack her veto of a plan to give tax breaks to reimburse donors for contributions to Opportunity Scholarships for private school tuition. Democrats oppose the scholarships, saying the scholarships open the door to school vouchers and circumvent a state ban on using public funds for private schools.

With voters frustrated over pandemic-related school closures, Whitmer’s veto provides a point of attack for James Craig, the former Detroit police chief and current frontrunner for the Republican nomination, Reckhow said.

“Republicans’ answer for a long time has been choice – choice in terms of vouchers, choice in terms of charters, choice in terms of home school,” she said. “The Opportunity Scholarship debate is a particular opening for Craig to advocate for more choice.”

Other key issues

Here are a few more issues we’ll be paying attention to this year:

- Mask mandates may continue to be a controversial political issue, as some school districts relax their mandates now that vaccines are available for children over 5. In districts that don’t have a mask mandate, we expect to see some parents push for a requirement in the wake of the COVID surge.

- Lawmakers likely will continue trying to push legislation that would ban critical race theory in the state’s K-12 schools. The theory is a college-level academic framework that explores the lingering effects of centuries of white supremacy and racist policies that disadvantage people of color. Though there is little evidence it is being taught in K-12 schools, Republican lawmakers in Michigan and in many other states across the country have made banning it a priority.

- The surging omicron variant will likely bring more discussions about whether schools should try more aggressive ways to keep buildings open. Already, there is more regular testing of students and staff in schools. Some districts have instituted test-to-stay programs, which require students be tested for COVID in order to remain in the classroom. One such new initiative goes into effect in Detroit on Jan. 31. There also will likely be debate about whether schools can require students to be vaccinated. In the Detroit district, staff are required to be vaccinated by Feb. 18 and Superintendent Nikolai Vitti wants to extend that mandate to students. He told Chalkbeat last week that if state lawmakers won’t require vaccines, then they should “get out of the way” of districts that want to implement such policies on their own. “Don’t put us in a straitjacket to do what we need to do to allow school to move forward with greater consistency.”

This article was originally posted on These are the big Michigan education issues we’re watching in 2022

More Stories

More West Virginia schools will participate in opioid abuse prevention program

Pennsylvania is increasingly underfunding special education, report finds

Memphis’ Kingsbury High School community steps up call for changes