Newly released state data shows high testing rates in Native communities, low rates in some rural counties

As the COVID-19 pandemic has progressed in Montana, no two parts of the state have been afflicted in quite the same way. While the state’s total case count figure — 4,314 and counting as of Aug. 4 — drives headlines, communities ranging from Browning to Bozeman to Miles City have seen their coronavirus stories play out along particular lines.

As such, county-level figures can be more useful than statewide statistics for Montanans looking to understand how the virus is hitting close to home. County-level case counts, published by many local health departments and available on the state’s official COVID-19 dashboard since early in the outbreak, provide perhaps the clearest measure of the virus’ local presence.

But as Montanans try to make sense of their local numbers, a key piece of the data puzzle — the number of COVID-19 tests conducted in each county — hasn’t been available, making it difficult to assess how thoroughly some corners of the state have been monitored for the disease. In April, an effort by Montana Free Press and other news outlets to compile testing numbers for each county identified significant gaps in the state’s efforts to track testing data.

Now, newly released data from the Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services fleshes out Montana’s coronavirus picture, with some caveats, by showing how many tests were administered in each of the state’s 56 counties week by week through July 18.

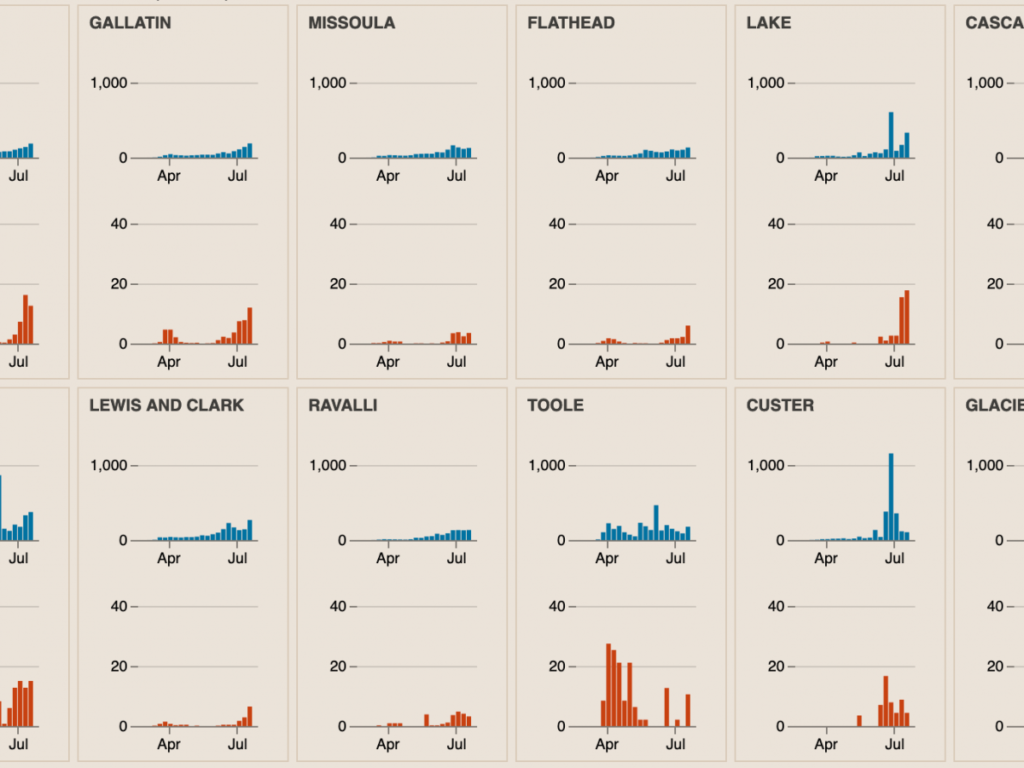

The figures show increasing testing rates over time in Montana’s urban counties, including Yellowstone (Billings), Gallatin (Bozeman) and Missoula, as the easing of early-pandemic supply shortages let public health workers ramp up their testing programs. Additionally, spikes from mass testing events are visible in several communities during weeks when large testing events took place.

Additionally, almost five months months into the pandemic, the reported testing rate between Montana’s most- and least-tested counties varies dramatically — the product of focused surveillance testing in high-risk Native American communities and what health officials say is the tendency for people in some low-population rural counties to go elsewhere for health care.

Glacier County, for example, has tallied a total of 7,129 tests among its 13,800 residents in state data current through July 24. That puts the county, which encompasses most of the Blackfeet Indian Reservation, at about 5,200 tests per 10,000 residents.

Judith Basin County east of Great Falls, in contrast, tallied 7 tests among its 2,000 residents, a testing rate of 35 tests per 10,000 residents (two of those tests came back positive). In Petroleum County, population 500, not a single COVID-19 test has been recorded as of July 24.

The data does come with some asterisks, meaning these figures may not align precisely with coronavirus data published in other places. For example, the weekly counts provided by the state health department are based on the date the tests were conducted — not, as is the case with many publicly available coronavirus statistics, the date results became available.

Importantly, the health department also says the counts reflect the counties where the tests were conducted, not necessarily the counties where the tested people live. So if, for example, a Judith Basin resident drove into Great Falls for a test at one of the city’s regional health care providers, they would have been tallied in Cascade County. That means the new data still isn’t a complete measure of how many people have been tested for the virus in particular communities, and may overstate the number of tests conducted on people who live in regional health care hubs.

Jim Murphy, the health department’s chief epidemiologist, pointed to that caveat as the likely explanation for low testing numbers reported for some rural counties

“When you look at a county that doesn’t show up much on there, I don’t think that should say anything about whether that county is not looking hard enough,” Murphy said. “There are some things we don’t know about their numbers.”

Murphy also said the state tracks COVID-19 hospitalizations and monitors emergency room admission data for reports of influenza-like symptoms, which gives epidemiologists other ways to catch an emerging outbreak.

The testing figures also include repeated tests conducted on the same patients, meaning the figures aren’t necessarily a precise reflection of how many people have been tested for the coronavirus. Murphy said he doesn’t have an exact count of the number of repeated tests in the state’s data, but believes they represent less than 5% of the total.

As Montana entered the early stages of its phased reopening in late April after Gov. Steve Bullock’s late-March stay-at-home order, the governor announced a push to scale up testing efforts to help inform the state’s pandemic response. In aggregate, the state has reached a 15,000-tests-per-week goal set by Bullock.

In addition to testing patients with coronavirus symptoms and people who’ve had contact with confirmed cases, the state has focused COVID-19 monitoring efforts on two settings with particularly vulnerable populations: nursing homes, which have seen devastating outbreaks in Montana and elsewhere, and tribal communities.

Testing events in tribal communities, where health officials have been concerned about crowded housing and pre-existing health conditions, are visible in week-by-week county testing counts. Big Horn County, for example, which spans most of the Crow Indian Reservation, reported 303 tests the week ending May 30. After testing events in Crow Agency and Lodge Grass the following week, it reported 1,151.

Mass testing events were held in June and July in communities including Poplar, Wolf Point, Lame Deer, Arlee, Pablo, Browning, Hays and Wolf Point, according to the state coronavirus task force.

Murphy also said that testing has in some cases been driven by local outbreaks, as contact tracing efforts tied to known cases kick in and front-line health care providers become more aggressive about ordering tests on more patients with virus activity confirmed in their communities.

Custer County, including Miles City, for example, posted relatively low weekly testing numbers through mid-June, when a local outbreak was identified. It reported 46 tests the week ending June 13, eight of them returning positive. The following week, 432 tests identified 19 coronavirus cases. The next week after that, the county registered 1,317 tests.

“It’s highly influenced by what clinicians are doing and what they’re seeing in nearby communities or their own communities,” Murphy said. “Testing goes up dramatically if they’re worried they might miss a diagnosis.”

The flip side, Murphy added, is that it isn’t necessarily a problem if a community without a known outbreak isn’t doing a lot of testing.

“They simply may not have any reason to be looking really hard, and given the fact that testing still requires some resources, we appreciate that,” he said. “If they don’t need to be testing, they shouldn’t be.”

The data used for this story, obtained by MTFP July 30 via a records request, is available for download here, as are print- and web-optimized versions of story graphics for news outlets looking to republish this piece under MTFP’s story-sharing terms. The code used to produce these graphics is available here.

More Stories

Kemp signs executive order to extend suspension of Georgia’s motor fuel tax until July 14

Florida continues to outperform U.S. in economic success

Newsom announces funding expansion for reproductive services